2Department of Cardiology, University of Health Sciences, Koşuyolu Heart Training and Research Hospital, İstanbul, Türkiye

3Department of Cardiology, Medipol University Faculty of Medicine, İstanbul, Türkiye

4Department of Cardiology, Ahi Evren Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery Training and Research Hospital, Trabzon, Türkiye

Abstract

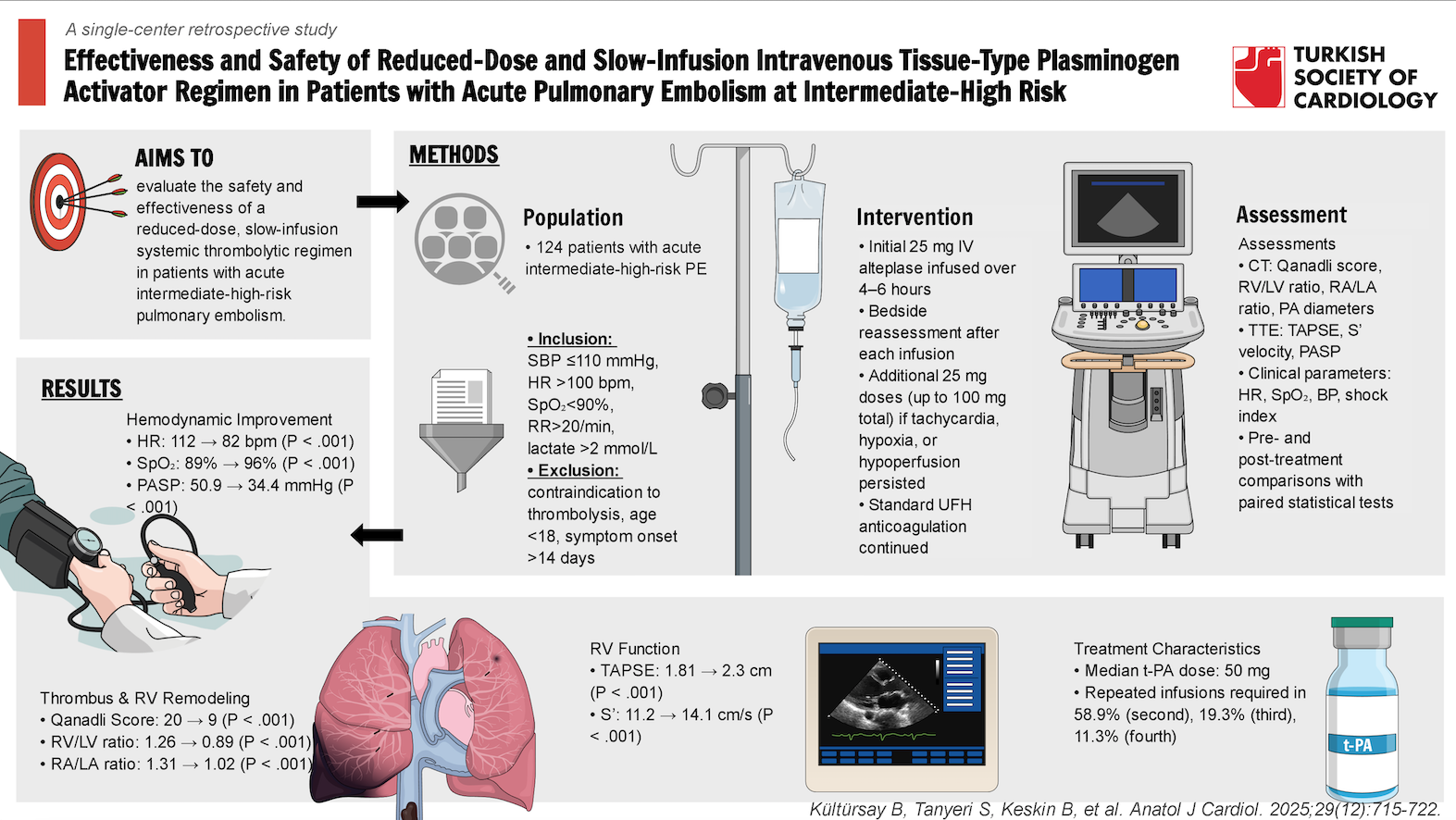

Background: Intermediate-high-risk (IHR) pulmonary embolism (PE) is defined by right ventricular (RV) dysfunction and elevated cardiac troponin in the absence of hemodynamic instability. While full-dose thrombolysis may improve outcomes, it poses a high bleeding risk. This study assessed the safety and efficacy of a reduced-dose, slow-infusion thrombolytic regimen.

Methods: This single-center retrospective study included 124 patients with acute IHR PE who met at least one of the following criteria: systolic blood pressure ≤110 mm Hg, heart rate >100 bpm, SpO2 <90% on room air, respiratory rate >20/min, or lactate >2 mmol/L. Patients with contraindications to thrombolysis or symptom onset >14 days were excluded. Patients received 25 mg intravenous alteplase (t-PA) infused over 4-6 hours, along with standard anticoagulation according to the institutional protocol. Following the initial dose, a repeat infusion of 25 mg over 4-6 hours was administered if tachycardia, hypoxia, or signs of organ hypoperfusion persisted on re-evaluation.

Results: Syncope was the presenting symptom in 27.4%, and 49.2% had deep vein thrombosis. Median t-PA dose was 50 mg and median infusion duration was 6 hours. Significant improvements were observed in RV and RA size/function, thrombus burden, and clinical parameters (all P < .001). Qanadli score and RV/LV ratio decreased by 55% and 29%, respectively. Major and minor bleeding occurred in 4.8% and 3.2%. In-hospital mortality was 4.8%; 12-month survival was 89.5%. Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension developed in 3.2%.

Conclusion: Low-dose, slow-infusion t-PA therapy appears effective and well-tolerated, offering hemodynamic and clinical benefit with fewer bleeding complications in patients with IHR PE.

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

- This study evaluates a low-dose, slow-infusion alteplase protocol in intermediate-high risk pulmonary embolism (PE) patients. The median t-PA dose was 50 mg and median infusion duration was 6 hours.

- Most patients required more than 1 infusion of 25 mg alteplase for adequate response.

- Treatment led to significant improvements in hemodynamic parameters, including heart rate, oxygen saturation, pulmonary artery systolic pressure, right ventricular/left ventricular ratio, and Qanadli score.

- Major bleeding occurred in only 4.8% of patients; intracranial hemorrhage occurred in 0.8%.

- In-hospital mortality was 4.8%; 12-month survival was 89.5%. Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension developed in 3.2%.

- These findings support that low-dose slow-infusion thrombolysis is a safe and effective alternative in managing IHR PE.

Introduction

High-risk (HR) pulmonary embolism (PE), a lethal condition, presents with hemodynamic instability and requires urgent reperfusion treatment. Intermediate-high-risk (IHR) PE, on the other hand, presents with right ventricular (RV) dysfunction and elevated circulating cardiac troponin levels, even when the patient appears hemodynamically stable at the time of presentation. However, there is a residual risk of deterioration toward hemodynamic instability in patients at IHR status. Although full-dose systemic thrombolytic treatment (STT) is effective in reducing all-cause mortality and preventing hemodynamic collapse in these patients, this treatment is also associated with increased risks of intracranial or other life-threatening bleeding, which has previously been confirmed in 2 meta-analyses.1-

Considering the balance between benefits and risks, reduced-dose STT regimens are gaining popularity in clinical practice globally. This study aimed to evaluate the safety of a reduced-dose STT regimen while maintaining effective reperfusion in patients with acute IHR PE.

Methods

Design

Between 2012 and April 2025, a total of 976 patients with acute PE were admitted to the center. The systematic work-up for the diagnosis of acute PE, and initial risk stratification comprising the multidetector contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) angiography and transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) assessments, PE severity indexes, and biomarker evaluation has been based on the criteria recommended by the European Society of Cardiology/European Respiratory Society 2019 PE guidelines.3 Among these, patients identified as IHR were screened, and 124 patients who met the inclusion criteria were ultimately included in the study (

The inclusion criteria were at least one of the following: systolic blood pressure ≤ 110 mm Hg, heart rate > 100 bpm, pulse oximetric saturation (SpO2) < 90% on room air, respiratory rate >20 breaths per minute, or serum lactate >2 mmol/L. Exclusion criteria were the presence of any contraindication for STT, age < 18 years, and duration from symptom onset to PE diagnosis >14 days. The thrombolytic treatment strategy was implemented as part of an institutional protocol. According to the institutional protocol, patients who met the inclusion criteria and none of the exclusion criteria received initial weight-adjusted UFH, followed by a 25 mg intravenous infusion of tissue-type plasminogen activator (t-PA, alteplase) over 4-6 hours. After this first infusion, a bedside clinical reassessment was performed. If any of the following criteria were still present—heart rate > 100 bpm, SpO2 < 90%, or signs of organ hypoperfusion—a second 25 mg t-PA infusion was administered in the same manner. In the case of persistent clinical deterioration, repeated infusions were given according to the same dosing strategy.

Computed tomography images were acquired using 64-slice helical CT angiography (Toshiba Aquilion 64™, Toshiba Medical Systems Corp., Tokyo, Japan). A validated CT score for pulmonary arterial (PA) occlusion proposed by Qanadli et al5 [Qanadli score (QS)], RV to left ventricle (LV) ratio, RV diameter, right atrial to left atrial diameter ratio (RA/LA ratio), and main, left, and right PA diameters were measured from CT images. Pulmonary infarction is defined as a peripheral wedge-shaped pulmonary consolidation in a hypoperfused segment of the lung. The CT images were evaluated at admission and 72-96 hours after the initiation of treatment. The TTE was performed on all patients on the first day of admission and repeated at discharge. Tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE) and tissue Doppler (S’) measurements were obtained to assess RV function in TTE, and estimated pulmonary artery systolic pressures (PASP) were calculated from the tricuspid regurgitation jet. All measurements and assessments were made in accordance with the American Society of Echocardiography guidelines.6

The data were collected retrospectively from hospital records. Given the retrospective design and inclusion of the entire eligible patient cohort, power analysis was not performed. Follow-up data were obtained through review of electronic medical records and hospital databases. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee (Approval No: 2025/06/1093, Approval Date: April 22, 2025), and all procedures were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Clinical effectiveness outcomes were all-cause mortality in 30 days, resolution of thrombus on CT as assessed by QS, and reduction in right ventricle to left ventricle diameter ratio (RV/LVr) on CT. For safety outcomes, major bleeding was defined as overt bleeding associated with a fall in the hemoglobin level of at least 2 g/dL, or with transfusion of 2 units of packed red blood cells, or involvement of a critical site.7 Clinically overt bleeding not fulfilling the criteria for major bleeding was classified as a minor bleeding complication.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using R version 4.3.1 (R Project, Vienna, Austria) and Jamovi Version 2.6.19.0. Normally distributed continuous data were expressed as mean and standard deviation values, whereas non-normally distributed data were expressed as medians and interquartile ranges, and categorical data were described as absolute and percentage values. Normality of the data was determined using histograms and the Shapiro–Wilk test. The paired sample

Results

Baseline Characteristics

Patient characteristics are summarized in

Prior to treatment, the mean heart rate was 112 ± 16.6 beats per minute, systolic blood pressure was 123 ± 14.9 mm Hg, and SpO2 was 89% (85%-93%). Laboratory analysis revealed median serum lactate levels of 2.35 mmol/L (1.6-2.9), troponin levels of 0.096 ng/mL (0.04-0.27), D-dimer levels of 9.82 U/mL (5.13-18.5), and C-reactive protein levels of 23.1 mg/L (11.6-45.3).

Clinical and Hemodynamic Outcomes

Mean and median doses of t-PA were 47.5 ± 24.1 and 50 (range: 25-50) mg, respectively. Mean and median duration of low-dose t-PA infusions were 7.44 ± 5.31 and 6 (range: 4-10) hours, respectively. Second, third, and fourth t-PA infusions were required in 73 patients (58.9%), 24 patients (19.3%), and 14 patients (11.3%), respectively. The administered overall t-PA doses were 25 mg in 51 patients (41.1%), 50 mg in 49 patients (39.5%), 75 mg in 10 patients (8.0%), and 100 mg in 14 patients (11.3%) (

Following the low-dose tPA infusion(s), significant improvements were observed in clinical and hemodynamic status, PA thrombotic obstruction, and RV function (

Primary Clinical Outcomes and Bleeding Complications

The observed in-hospital mortality rate was 4.8%, with 2 fatalities (1.6%) attributed to major bleeding and 4 (3.2%) due to hemodynamic decompensation. Importantly, no cases of recurrent PE or hemodynamic deterioration were recorded during the 30-day follow-up period. Notably, only 1 patient (0.8%) experienced intracranial (cerebellar) hemorrhage, which did not require surgical intervention, and the patient was discharged without neurological sequelae. Among the 6 major bleedings, 1 occurred after 100 mg t-PA infusion, 4 after 50 mg, and 1 after 25 mg.

Median follow-up duration was 3045 (2563-3096) days, and the estimated 12-month overall survival rate was 89.52% (95% CI: 84.28%-95.07%) (

Discussion

This study provides compelling evidence that a low-dose, slow-infusion tPA regimen offers a favorable alternative in the management of IHR PE, while maintaining the clinical and hemodynamic benefits of full-dose STT and mitigating bleeding risks.

The fundamental goal of thrombolysis in PE is rapid pulmonary reperfusion and RV unloading, preventing hemodynamic deterioration and RV failure. However, the management of IHR PE presents a significant therapeutic challenge, balancing the need for effective reperfusion therapy against the risk of major bleeding complications. While STT remains a recommended option in select cases, concerns over hemorrhagic events have driven the exploration of alternative dosing strategies.

In this study, the inclusion criteria were designed to better define the upper zone of IHR PE patients, adopting parameters from the PEITHO trial’s subgroup analysis. This approach aimed to capture patients with subtle yet clinically meaningful hemodynamic compromise, who may benefit from early reperfusion therapy but are at elevated bleeding risk with full-dose STT.1

The median administered t-PA dose was 50 mg (range: 25-50 mg), with a mean of 47.5 ± 24.1 mg. The median infusion duration was 6 hours (range: 4-10 hours), and the mean was 7.4 ± 5.3 hours. Multiple infusions were needed: 58.9% had a second dose, 19.3% a third, and 11.3% a fourth. Doses of 25 mg and 50 mg were used in 41.1% and 39.5% of patients, respectively. The rest required cumulative doses of 75 mg or more. The study’s mortality rate was lower than that reported in the fibrinolytic arm of the PEITHO trial, suggesting that low-dose tPA may reduce risk effectively with better safety. Major and minor bleeding rates were 4.8% and 3.2%, respectively, much lower than the 9%-20% major bleeding rates reported in full-dose, short-infusion STT studies.1-

Compared to both STT and ultrasound-assisted catheter-directed thrombolysis (USAT), the cohort’s mortality was similar to previous reports, but major and minor bleeding rates were lower than 5.5% and 6.9%, respectively.9 Compared to those who underwent AngioJet rheolytic thrombectomy, the low-dose, slow-infusion t-PA regimen was associated with lower mortality and reduced rates of both major and minor bleeding while maintaining effective reperfusion.10,

Significant reductions in PASP, RV/LV, and RA/LA ratios and improvements in TAPSE were observed, suggesting that even low-dose t-PA can improve RV function impaired by thrombotic pressure overload. These findings are consistent with prior evidence suggesting that effective pulmonary thrombus resolution can be achieved with lower doses of thrombolytics, thereby challenging the conventional reliance on full-dose STT regimens.12-

Patients with worse baseline hemodynamics showed marked decreases in heart rate and modified shock index soon after low-dose tPA, indicating effective restoration of cardiac function without losing fibrinolytic effect.

Beyond the immediate hemodynamic improvements, one of the most critical long-term concerns in PE survivors is the development of CTEPH. While early and effective thrombus resolution is hypothesized to reduce this risk, long-term data remain inconclusive, and STT offers no benefit over standard anticoagulation in preventing progression to CTEPH, as demonstrated in the PEITHO trial.1,

The historical reliance on full-dose STT regimens has been predicated on the assumption that higher doses yield superior clot resolution. However, accumulating evidence, including the study, suggests that this approach may not be universally necessary. Low-dose regimens have been shown in multiple trials to reduce mortality and morbidity, indicating that a one-size-fits-all approach may not suit IHR PE.15,

Limitations, Clinical Implications, and Future Directions

The findings of this study suggest a rationale for integrating low-dose, slow-infusion STT with t-PA into routine management strategies for IHR PE patients. The balance between hemodynamic efficacy and safety makes it an attractive alternative to both full-dose STT and anticoagulation alone. However, this study has several limitations. First, its retrospective and single-center design may introduce selection bias and limit the generalizability of the findings to broader patient populations and different healthcare settings. Second, the absence of a direct comparator group reduces the ability to draw definitive conclusions regarding the relative effectiveness or superiority of the reduced-dose, slow-infusion regimen.

Future prospective, randomized trials with extended follow-up are essential to determine whether the acute benefits of low-dose thrombolysis translate into durable, long-term advantages, including a potential reduction in CTEPH incidence.24-

Additionally, stratified treatment algorithms—taking into account baseline hemodynamic status, bleeding risk, and RV function—may optimize patient selection, further individualizing management in this setting. The results of the ongoing aforementioned trials are expected to provide answers to these questions.

Conclusion

This study provides robust evidence that low-dose, slow-infusion STT with t-PA offers a safe and effective alternative to full-dose STT regimens in IHR PE patients. These findings align with an emerging body of literature suggesting that less-intensive fibrinolytic strategies can maintain efficacy while dramatically improving safety outcomes. With further validation, this approach could transform care for IHR PE.

Footnotes

References

- Meyer G, Vicaut E, Danays T. Fibrinolysis for patients with intermediate-risk pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(15):1402-1411.

- Marti C, John G, Konstantinides S. Systemic thrombolytic therapy for acute pulmonary embolism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Heart J. 2015;36(10):605-614.

- Chatterjee S, Chakraborty A, Weinberg I. Thrombolysis for pulmonary embolism and risk of all-cause mortality, major bleeding, and intracranial hemorrhage: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2014;311(23):2414-2421.

- Konstantinides SV, Meyer G, Becattini C. 2019 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism developed in collaboration with the European Respiratory Society (ERS). Eur Heart J. 2020;41(4):543-603.

- Qanadli SD, El Hajjam M, Vieillard-Baron A. New CT index to quantify arterial obstruction in pulmonary embolism: comparison with angiographic index and echocardiography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;176(6):1415-1420.

- Mukherjee M, Rudski LG, Addetia K. Guidelines for the echocardiographic assessment of the right heart in adults and special considerations in pulmonary hypertension: recommendations from the American Society of Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2025;38(3):141-186.

- Schulman S, Kearon C. Definition of major bleeding in clinical investigations of antihemostatic medicinal products in non-surgical patients. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3(4):692-694.

- Türkday Derebey S, Tokgöz HC, Keskin B. A new index for the prediction of in-hospital mortality in patients with acute pulmonary embolism: the modified shock index. Anatol J Cardiol. 2023;27(5):282-289.

- Kaymaz C, Akbal OY, Tanboga IH. Ultrasound-assisted catheter-directed thrombolysis in high-risk and intermediatehigh-risk pulmonary embolism: a meta-analysis. Curr Vasc Pharmacol. 2018;16(2):179-189.

- Akbal ÖY, Keskin B, Tokgöz HC. A seven-year single-center experience on AngioJet rheolytic thrombectomy in patients with pulmonary embolism at high risk and intermediate-high risk. Anatol J Cardiol. 2021;25(12):902-911.

- Kaymaz C, Kültürsay B, Tokgöz HC. Is it time to reappraise for black-box warning on AngioJet rheolytic thrombectomy in patients with pulmonary embolism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Anatol J Cardiol. 2024;28(6):264-272.

- Sharifi M, Bay C, Skrocki L, Rahimi F, Mehdipour M. “MOPETT” Investigators. Moderate pulmonary embolism treated with thrombolysis (from the “MOPETT” Trial). Am J Cardiol. 2013;111(2):273-277.

- Zhang LY, Gao BA, Jin Z. Clinical efficacy of low dose recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator for the treatment of acute intermediate-risk pulmonary embolism. Saudi Med J. 2018;39(11):1090-1095.

- Goldhaber SZ, Agnelli G, Levine MN. Reduced dose bolus alteplase vs conventional alteplase infusion for pulmonary embolism thrombolysis. An international multicenter randomized trial. The Bolus Alteplase Pulmonary Embolism Group. Chest. 1994;106(3):718-724.

- Wang C, Zhai Z, Yang Y. Efficacy and safety of low dose recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator for the treatment of acute pulmonary thromboembolism: a randomized, multicenter, controlled trial. Chest. 2010;137(2):254-262.

- Zhang Z, Zhai ZG, Liang LR, Liu FF, Yang YH, Wang C. Lower dosage of recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator (rt-PA) in the treatment of acute pulmonary embolism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thromb Res. 2014;133(3):357-363.

- Layman SN, Guidry TJ, Gillion AR. Low-dose alteplase for the treatment of submassive pulmonary embolism: a case series. J Pharm Pract. 2020;33(5):708-711.

- Konstantinides SV, Vicaut E, Danays T. Impact of thrombolytic therapy on the long-term outcome of intermediate-risk pulmonary embolism. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(12):1536-1544.

- Lio KU, Bashir R, Lakhter V, Li S, Panaro J, Rali P. Impact of reperfusion therapies on clot resolution and long-term outcomes in patients with pulmonary embolism. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2024;12(3):101823-.

- Fang A, Mayorga-Carlin M, Han P. Risk factors and treatment interventions associated with incomplete thrombus resolution and pulmonary hypertension after pulmonary embolism. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2024;12(1):101665-.

- Kato F, Tanabe N, Ishida K. Coagulation-fibrinolysis system and postoperative outcomes of patients with chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Circ J. 2016;80(4):970-979.

- Piazza G. Advanced management of intermediate- and high-risk pulmonary embolism: JACC focus seminar. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76(18):2117-2127.

- Kaymaz C, Tokgöz HC, Kültürsay B. Current insights for catheter-directed therapies in acute pulmonary embolism: systematic review and our single-center experience. Anatol J Cardiol. 2023;27(10):557-566.

- Sanchez O, Charles-Nelson A, Ageno W. Reduced-Dose intravenous Thrombolysis for Acute Intermediate-High-risk Pulmonary Embolism: rationale and Design of the Pulmonary Embolism International THrOmbolysis (PEITHO)-3 trial. Thromb Haemost. 2022;122(5):857-866.

- Klok FA, Piazza G, Sharp ASP. Ultrasound-facilitated, catheter-directed thrombolysis vs anticoagulation alone for acute intermediate-high-risk pulmonary embolism: rationale and design of the HI-PEITHO study. Am Heart J. 2022;251():43-53.

- Kjærgaard J, Carlsen J, Sonne-Holm E. A randomized trial of low-dose thrombolysis, ultrasound-assisted thrombolysis, or heparin for intermediate-high risk pulmonary embolism-the STRATIFY trial: design and statistical analysis plan. Trials. 2024;25(1):853-.

- Kucher N, Boekstegers P, Müller OJ. Randomized, controlled trial of ultrasound-assisted catheter-directed thrombolysis for acute intermediate-risk pulmonary embolism. Circulation. 2014;129(4):479-486.

- Piazza G, Hohlfelder B, Jaff MR. A prospective, single-arm, multicenter trial of ultrasound-facilitated, catheter-directed, low-dose fibrinolysis for acute massive and submassive pulmonary embolism: the SEATTLE II study. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;8(10):1382-1392.

- Tapson VF, Sterling K, Jones N. A randomized trial of the optimum duration of acoustic pulse thrombolysis procedure in acute intermediate-risk pulmonary embolism: the OPTALYSE PE trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;11(14):1401-1410.

- Kaymaz C, Akbal OY, Keskin B. An eight-year, single-center experience on ultrasound assisted thrombolysis with moderate-dose, slow-infusion regimen in pulmonary embolism. Curr Vasc Pharmacol. 2022;20(4):370-378.

- Kültürsay B, Keskin B, Tanyeri S. Ultrasound-assisted catheter-directed thrombolytic therapy vs. anticoagulation in acute intermediate-high risk pulmonary embolism: a quasi-experimental study. Anatol J Cardiol. 2025;29(6):312-320.

- Kaymaz C, Akbal OY, Hakgor A. A five-year, single-centre experience on ultrasound-assisted, catheter-directed thrombolysis in patients with pulmonary embolism at high risk and intermediate to high risk. EuroIntervention. 2018;14(10):1136-1143.